The Soft Labor Questionnaire: Leonardo Bravo

Welcome to Soft Labor, the namesake publication of Soft Labor, a strategic consultancy for organizations, designers, and the culture industry led by Sarah Hromack-Chan. Soft Labor is a publication about creative labor—what it is, what it looks like, and how it has and will continue to change. Did someone forward you this publication? Subscribe, read our archives, or email us at info@softlabor.biz.

The Soft Labor Questionnaire, is simply that: A brief series of questions we’ve asked comrades in the field to answer about their own working experiences. Would you like to respond to the Soft Labor Questionnaire? Go right ahead and do so.

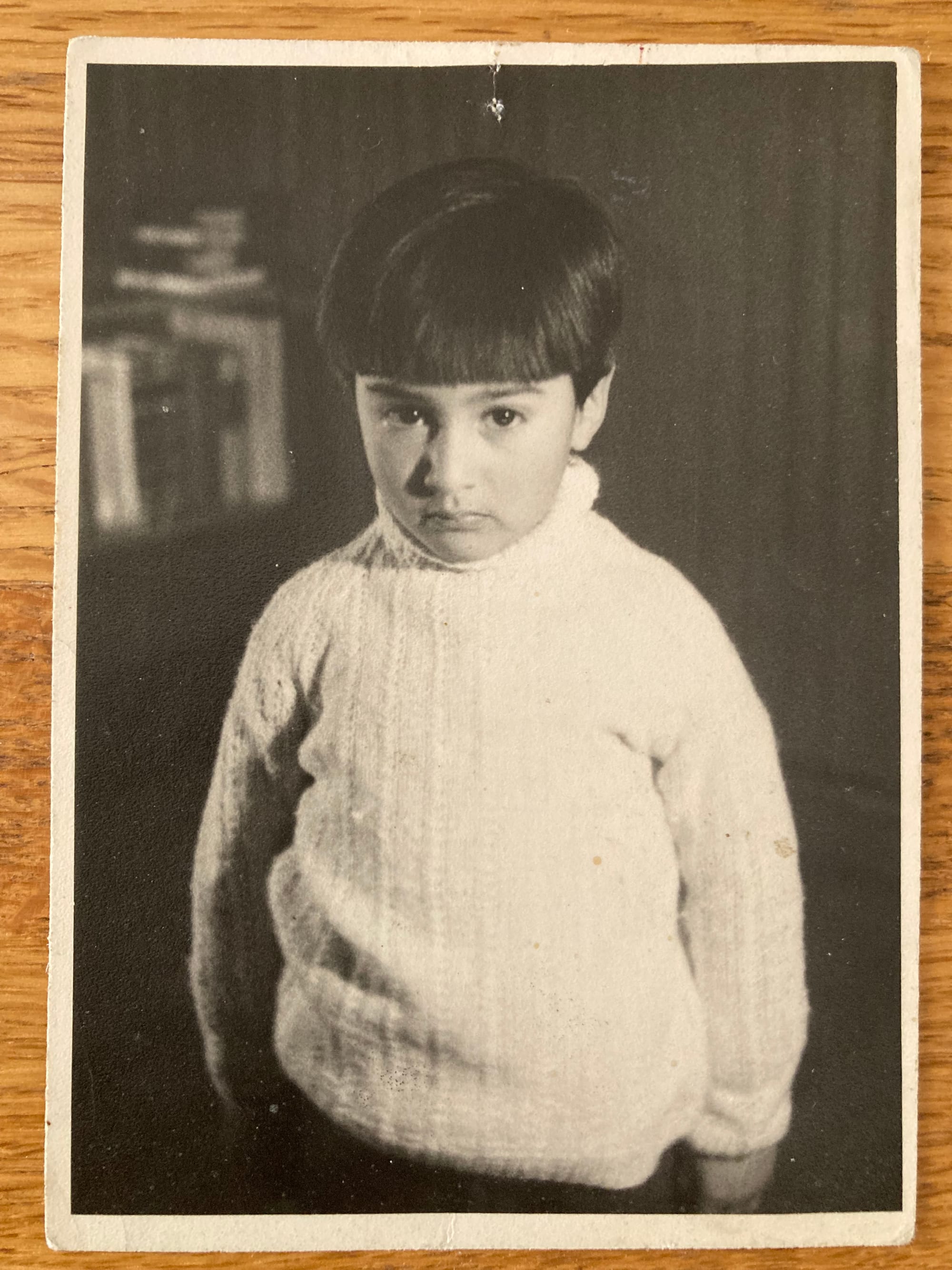

Today's respondent is Leonardo Bravo. Leonardo is an artist, educator, and curator. His work in the arts sector has exemplified building public and private partnerships that highlight the power of the arts to transform and catalyze vulnerable and underserved communities. He has held leadership positions at various cultural institutions in Los Angeles, has taught at UCLA's World Arts Culture and Dance Department, and is currently the Director, Public Engagement within MoMA's Learning and Engagement Department where he oversees public programs within the museum and community and civic engagement initiatives. He was also the founder and organizer of Big City Forum, an interdisciplinary, social practice and curatorial research project in Los Angeles that brings attention to emergent practices across design, architecture, and the arts.

Bravo's work is on view now at Kates-Ferri Projects, 563 Grand Street, NYC.

Tell us about the first job you ever did for money.

In high school, I worked as a deckhand on a 40-foot yacht docked in Newport Harbor. The boat belonged to a well-to-do family, and I got the job through my mother, who cleaned houses for several families in that part of Southern California. Looking back, it was an unusual experience—a teenager who had recently immigrated from Chile, navigating feelings of displacement and loss, suddenly working among the wealthy in a world so different from my own. Yet, that job offered me a sense of stability and purpose. Each week, I washed down the boat, polished the railings, and scrubbed every surface until it shone. It taught me discipline, responsibility, and the satisfaction of seeing a task through to the end.

The older couple who owned the yacht were not only successful but also kind and empathetic toward me. We shared some memorable moments, especially during weekend trips to Catalina Island. They loved to party there, and more than once I found myself taking the dinghy out late at night to ferry them back to the yacht after they’d had a bit too much to drink. Those were different times—but ones I remember fondly.

Is your current work related to what you studied in school? If so, how? Or, how not?

I earned both my BFA and MFA in Los Angeles, focusing on art and critical studies—an experience that has profoundly shaped the course of my life and career ever since. During that time, I was fortunate to have exceptional mentors and advisors who deeply influenced my perspective and way of thinking. Their guidance continues to inform how I see the world, particularly my belief that the arts lie at the heart of human experience and have the power to inspire engagement, reflection, and change.

What cultural touchpoint—music, art, literature, etc.—has informed your practice the most? How?

This one’s hard to pin down, because my cultural touchpoints have always been fluid—shifting and never static. Culture, in all its forms, has been a deep well I keep returning to. But if there’s one thread that’s carried me through, it’s music and how it's shaped how I see, feel, and move through the world.

I grew up in Chile with a father who was a gifted classical violinist. He taught me to listen deeply, to hear the subtle spaces between sounds. But as a teenager, I turned away from it. I was restless, angry, searching for something raw and unscripted. I found myself drawn to music built on dissonance and distortion—uneven, jagged, alive. Those sounds mirrored what I felt inside and became a language of defiance, a way to claim something entirely my own.

Over time, another current pulled at me: bass-heavy music, where the drum and bass speak to each other in a kind of ancient dialogue. There’s something elemental in that exchange—something that vibrates in the body before it ever reaches the mind. I think that’s why I’m still captivated by moments like Detroit techno in the ’80s and ’90s, where Black artists forged soundscapes that were both ancestral and futuristic. That tension—between memory and possibility—feels like home to me.

What is the most rewarding aspect of working in your industry? The most challenging?

Working in the arts—and within cultural institutions and museums—has been a way for me to explore and test ideas about how art sits at the very heart of human experience, with the power to inspire engagement, reflection, and change. It’s been a long and evolving journey, but I’m deeply grateful for the opportunities I’ve had to lead, design, and facilitate programs that bring communities together through the arts—creating spaces for connection, dialogue, and shared humanity. For me, these moments represent a counterpoint to division, an invitation to be together in meaningful ways.

It’s been especially powerful to use the support of institutions to build experiences that expand what museums and cultural spaces can be: more welcoming, more porous, more reflective of our cultural complexities and lived realities. What’s been most affirming, though, is doing this work from my perspective as a person of color—bringing empathy, sensitivity, and a lived understanding of nuance to the ever-evolving practice of community engagement through the arts.

Has AI impacted your work? How?

While it may not define the larger arc of my work, I’m drawn to artists who use generative data and AI as new mediums for creative expression. There’s something thrilling about the imaginative leap AI allows, a sense of opening doors to possibilities that were previously unimaginable. At the same time, I remain alert to its weight—the ways it can be harnessed to impose control, to codify hierarchy, or to serve the extractive logic of late capitalism. That tension, between boundless creativity and caution, makes the work all the more compelling.

What advice would you give to someone starting a career in your industry?

My advice is to stay agile, be precise, and embrace multiplicity in your approach. Change is the only constant, and the ability to navigate its ebb and flow will serve you well.

What are you obsessed with that has little-to-nothing to do with "work"?

Since moving to New York a couple of years ago, I joined a boxing gym in Chelsea—a long-held wish of mine to engage deeply with boxing as a practice. Back in LA, I had spent a lot of time doing yoga and other physical training, but boxing has captured me in a completely different way. It challenges me not just physically, but mentally, demanding total presence and focus in the moment. The training is rigorous: building muscle memory while refining neural pathways, cultivating a sense of fluidity, agility, and precision that evolves with every repetition.

Boxing also pushes you to confront difficulty head-on, to move through discomfort, and to see challenges through to the end. In this way, it’s more than a workout—it’s a practice of self-awareness, resilience, and agency, a way to face yourself with both strength and clarity.